Hand crews are the backbone of America’s fire suppression efforts. America would be doomed without them. Is that hyperbole? Maybe. But the point that must be made is that the men and women who serve on Hotshot Crews, Type 2 and Type 2 Initial Attack Crews, bear the brunt of the physical labor that goes into fighting a wildfire. When you’re watching television coverage of a fire, and you see a group of firefighters, swinging tools, punching in some gnarly line while sucking in dust and smoke, 9 times out of 10, you’re looking at a handcrew doing their thing.

Hand crews are the backbone of America’s fire suppression efforts. America would be doomed without them. Is that hyperbole? Maybe. But the point that must be made is that the men and women who serve on Hotshot Crews, Type 2 and Type 2 Initial Attack Crews, bear the brunt of the physical labor that goes into fighting a wildfire. When you’re watching television coverage of a fire, and you see a group of firefighters, swinging tools, punching in some gnarly line while sucking in dust and smoke, 9 times out of 10, you’re looking at a handcrew doing their thing.

It’s a hard job. It’s not for everyone. But for those who have done it, it’s the way firefighting is supposed to be. No water. No hoses. Just you. Your tool. And twenty of your best friends. Game on, Fire.

Challenge Accepted.

As you can see, I’m tremendously biased towards hand crews. I will admit that with a smile! I spent my time in fire exclusively on hand crews. And to this day, I wouldn’t have done it any different. Though maybe I wish I had given smokejumping a shot, or tried to do a season on a helicopter. That aside, being on a handcrew is one of the best experiences you can have in fire.

Four Reasons To Be On a Handcrew:

- The Crew. Twenty People who will all go from strangers to friends in 6 months. Some might even become best friends.

- The Experience. You’ll be assigned to do the hardest work. But it will also be the most rewarding. If you’re on a hotshot crew, and the Incident Commander orders some backfiring to be done at night, guess who’s getting the drip torches? You are.

- The Respect. Being on a handcrew is hard work. And if you’re able to hack it on handcrew, that will give you credibility for whatever you do next. Almost every single smokejumper has spent multiple years on a hotshot crew.

- The Action. You’re going to see more fire on a handcrew than you will on an engine crew, a wildland fire module, a fuels crew, etc. If you want to slay some fire-breathing dragons, handcrews are where you want to be.

Alright, so you’re now fired up about handcrews! Great. Mission Accomplished! Let’s get a few things squared away. First, what what’s the difference between a Type I Crew and a Type 2 Crew? And what’s a hotshot crew?

First off, a hotshot crew is more formally known as a Type 1 Interagency Hotshot Crew (IHC). So when you hear Type 1 vs Type 2 crew, you can rephrase as “Hotshot crew vs. Type 2 crew”. As of 2018, there are currently more than 100 hotshot crews. Which means every year, around 2,000 men and women serve on hotshot crews. So it’s a relatively small community. For the sake of comparison, there are about 1,696 players in the NFL (32 teams x 53 Players = 1,696). Fortunately, you don’t need to be a physically-dominant alpha male to be on a hotshot crew. Heck, you don’t even need to go to college (though it’s not a bad idea to go college first, or during, of course!)

So where did the name “Hotshot” come from? Well, that’s a good question, and quite frankly, there’s a lot of debate about the its origins. There’s even debate about which crew was the first hotshot crew. According to the US Forest Service, “Hotshot crews were first established in Southern California in the late 1940s on the Cleveland and Angeles National Forests. They were called “Hotshot” crews because they worked on the hottest part of wildfires.” From what I’ve been able to gather, the Los Padres Hotshots, the El Cariso Hotshots, and the Del Rosa Hotshots all started either in 1946 or 1947 and can all be rightly considered as the original hotshot crews. Unfortunately, El Cariso was disbanded in 2018, but the Los Padres and Del Rosa are still going strong!

Besides a catchier name, what else separates a hotshot crew from Type 2 crew?

Leadership Qualifications: Hotshot crews have more experienced, more qualified leaders. Their Superintendent and Assistant Superintendent are both qualified ICT4, minimum. They will have Task Force and Strike Team leader qualifications. They will have three squad leaders, all certified at the Crew Boss level, with ICT5. A hotshot crew will also have at least two Senior or Lead Firefighters who are certified at the FFT1 level.

Crew Experience: 80% of the crew members on a hotshot crew have at least one year of experience. While the requirement for a Type 2 IA crew is only 60%. And for a standard, non-IA Type 2 crew, only 20% of the crew must be experienced. Also, it is mandatory that Type 1’s train as a team. Type 2 IA and Type 2 crews don’t have this requirement, and can be assembled by pulling together resources from a wildland fire module, fuels crew, engine crew, etc. on an as-needed basis. Hotshot crews have stronger crew cohesion because they work and train together as a unit.

Production Rate: Hotshots cut more line, faster, with better quality. That’s what hotshots are known for.

And, to a lesser extent, gear. Hotshot crews have more radios, don’t require transportation when they arrive onsite at an incident, and have purchasing authority so they can fend for themselves.

At the end of the day, what you’re getting with a hotshot crew is a brand. And a guarantee. There is less variability between hotshot crews and type 2 crews. Hotshot crews are held to a higher standard. And the quality is high and consistent. When an Incident Commander orders up a Type 2 crew, you might get an amazing crew. In awesome shape. With great leaders who, on a good day, might be able to outperform a lot of hotshot crews. But you could also get a group of folks with minimal fire experience, who have never worked together, and can only do the most basic of assignments, and with heavy supervision required. That’s the risk.

I was lucky enough to be on a Type 2 crew for two years that was run incredibly well. Crew 3 on the Plumas National Forest was led by Robert Daniels, who, through his hard work and high standards for excellence, ultimately got the crew certified as a Type 1 Interagency Hotshot Crew, and they’re now known as the Feather River Hotshots. From the beginning, he treated that crew as a hotshot crew, and we performed like a hotshot crew.

If you want to get more specific about the differences, feel free to dive into the Interagency Standards for Fire and Fire Aviation Resources. Everything you ever wanted to know (and more) about standards can be found in that pdf.

Physical Requirements:

In addition to the pack test (which must be passed at the Arduous level for all handcrew members), Hotshot Crews also require their firefighters be able to pass the following minimum qualifications:

- 1.5 mile run in a time of 10:35 or less

- 40 sit-ups in 60 seconds

- 25 pushups in 60 seconds

- Chin-ups, based on body weight

- More than 170 lbs. = 4 chin-ups

- 135-170 lbs. = 5 chin-ups

- 110-135 lbs. = 6 chin-ups

- Less than 110 lbs. = 7 chin-ups

Needless to say, the expectation is that you can far surpass these on Day 1.

A Day in the Life of a Hotshot on a Fire

0545: Rise and shine. It’s cold and dark and the last thing I want to do is leave the warmth of my sleeping bag. Hurry up and get pants on and boots laced up. Shake the tent of any heavy sleepers and tell them to get the hell up because I’m hungry.

0600: Line-out and walk to chow in tool order. Have a passing thought that you haven’t walked in “order’ anywhere since grade school and that it’s a bit ridiculous for grown men to do it. But keep it to yourself. You’re grumpy and sore.

0610: Cave-in and get the biscuits and gravy and scrambled eggs and bacon. Tomorrow you’ll get the oatmeal and fruit…tomorrow…Force myself to drink ½ gallon of water and a couple cups of coffee.

0630: While overhead goes to morning briefing, head over to the saw tent to pick-up a couple air filters, some extra chains, and a couple new bars. Grab a case of Gatorade.

0645: Do some maintenance on the saw, sharpen tools, and clean out the buggie.

0700: Circle up as a crew and go over the incident action plan for the day and review the crew’s assignment. Discuss expected weather and fire behavior. Dig the fact that the IC team put us on the gnarliest, ugliest part of the fire.

0730: Load-up and head out to the fireline.

0735: Despite three cups of firecamp coffee, fall asleep in the buggy

0830: Arrive on the incident, gear-up, check radios, and line-out.

0845: Hike-in.

0915: Fire-up the saws and start punching a highway through the woods. Classic hotshot line: 6’ saw cut and 3’ scrape. Enough clearance to move a convoy of elephants through.

1145: Finish third quart of water.

1300: Grab a bite to eat. Gripe about the sack lunches. Wish there were three more Capri-Suns in there, instead of a peanut butter and jelly sandwich.

1330: More line cutting.

1430: Afternoon weather moves in. Winds pick-up and change direction, and temperatures approach trigger points. Overhead convenes to discuss strategy and tactics. Crew shades up and sharpens tools. Decision is made to continue line construction. Post an extra look-out for safety, re-evaluate escape routes and safety zones, and change tactics from direct attack to parallel attack.

1630: Watch in awe as a stand of trees erupts into a giant volcano of fire. Think to myself this is the coolest damn job in the world. Then get yelled at by my squaddie to get my ass back to work, scrape is bogging down behind us.

1800: Bump-out.

1930: Pack a dip, clean saws, and sharpen tools.

2000: Grab dinner. Steak and mashed potatoes. Remarkably delicious. Gorge on cake, and wonder aloud where the hell they must have trucked this in from.

2030: Shoot the shit with a crew from a neighboring forest. Talk about how their season is going.

2100: Head back to the tents. Brush teeth. Drink ½ gallon of water. Talk to other crewmembers about some new fires popping up in Idaho, wonder if that’s where the next assignment will be once we put this fire to bed.

2200: Crawl back into your sleeping bag and set your alarm for 0545. Get ready to do it all over again.

Roles on a Handcrew

Superintendent: The superintendent leads the crew. It is his or her responsibility to keep the crew safe. The superintendent is rarely involved with actual line construction. The superintendent handles the majority of the administrative tasks on a fire (payroll, time keeping, expenses, finding hotels, etc.). On a fire, the superintendent will be monitoring multiple radio channels, and maintaining communication between the incident command team and the crew. He is the main point of contact. The superintendent is responsible for implementing the strategy that is given to the crew by the Incident Command Team. The Superintendent will sometimes be on the fireline with the crew, other times they might serving in the role of a lookout, overwatching a crew. Especially if the crew is in a canyon, or has limited visibility. Oftentimes, the superintendent will be pulled away from the crew to serve as a Division Boss, Safety Officer, or Burn Boss.

Captain / Assistant Superintendent: The Captain is responsible for running a module or a squad, usually consisting of up to ten firefighters. It is quite common for a hand crew to split into two squads during initial attack or mop up operations. On a small fire, a handcrew might show up to a fire, and the Superintendent might say something to the effect of “Crew Alpha – take the right flank, Crew Bravo, take the left flank.” It is the Captain’s job to establish the fireline. He will walk in front of the saw team, and identify how he wants to the line to be put in by flagging the trail or using his tool to blaze trees or scratch a path in the dirt. Additionally, he is constantly monitoring the fire’s behavior, and identifying and communicating to the crew escape routes and safety zones.

Squad Boss: (GS 6) The squad boss usually brings up the rear during fireline construction. They are responsible for quality control. They also might have a fusee that they’re using to burnout the small areas of green between the handline and the black.

Lead Firefighter / Senior Firefighter (GS 5): They’re usually working on their squad boss task book. In general, they have been a member of the crew for a few seasons. They might be a sawyer. They might also play the role of a Saw Boss at times. They will regularly be asked to command small modules firefighters to perform certain tasks.

Firefighter (GS 3/ GS 4): Everybody else. The grunts! The men and women who do the dirty work and make it happen.

Tool Order

On a handcrew, tool order refers to the way firefighters line out while hiking, and during fireline construction. Handcrews do just about everything in a prescribed fashion, including lining out for chow, which you will most likely do in tool order as well. If you’re new to the concept, you’ll find it a little weird at first. “Wait, we all just walk in a straight line, in the same order, always?” Yeah, kinda.

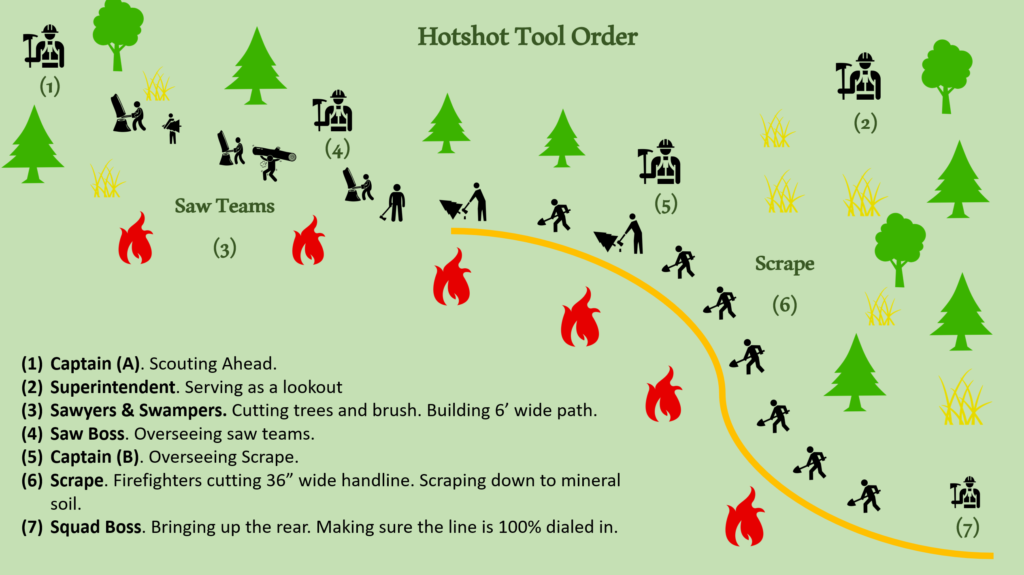

Below, we sketched out how 20 person hotshot crew might operate.

A few things to note. Tool orders, like formations in football, are flexible. So while the tool order above is pretty common, your crew might not run like that. And a crew very well might run different tool orders throughout the season, especially if they’re fighting fire in different terrains. If you’re fighting fire down in Southern California, and you know you’re going to be facing a lot of chaparral brush, you might opt to go with four saw teams. Especially knowing that the scrape might be a little easier than it might be in say, Idaho, where your scrape is going to be digging up roots every step of the way and you might only need one or two saw teams.

Crews will also have different perspectives on how to structure their scrape team for maximal efficiency. You might have a setup where you have a lead pulaski, followed by a scraping tool like a rhino, followed by another pulaski, followed by three or four rhinos and mcleods. Or you might have two or three pulaskis up front followed by the rhinos. At the end of the day, overhead will pick the the right tool order for that day. And that might mean you swing a different tool.

A few years ago, I spoke to my former squad boss on the Lassen Hotshots, Matt Holmstrom. While Matt is now Superintendent of the Lewis & Clark Hotshots, at the time he was serving as a Captain on the American River Hotshots. I asked him to describe how American River structured their tool order, and here was his response:

“As far as tool order goes we generally run 3 squads – makes us more flexible. This means that when we are together we run with the Superintendent and Captains up front – usually scouting or out on another special job, then saw boss, 3 saw teams, a lead tool (usually scrape/squadleader/line placement) then 3 pulaskis, and 6 scrapes with the last two being quality control.” – Matt Holmstrom

Recommended Reading:

Physical Training Advice – Check out our sister site, Hotshot Fitness